The Upper Extremities

Exam of the hands and arms is usually quite brief in the asymptomatic patient. Pay particular attention to the following:

The Hands:

- Appearance of hand and fingers: Any obvious deformity or discoloration?

Do they appear relatively red and well perfused or white/mottled?

For Additional Information See: Digital DDx: Nail Findings

- Nail shape and color (see below for discussion of cyanosis): Several examples

of common nail pathology are shown below.

Nicotine Staining

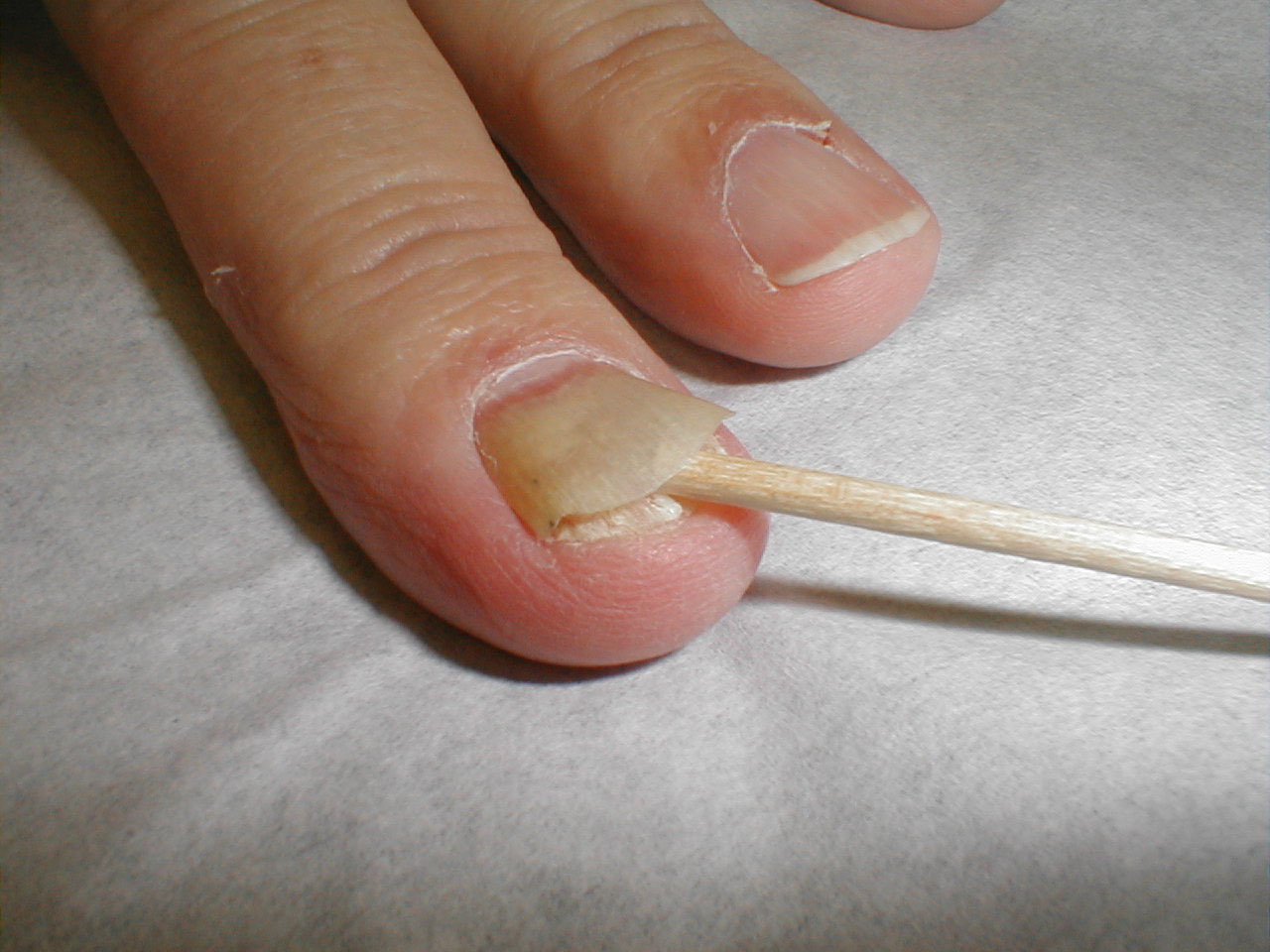

Nicotine Staining Onychomycosis:Fungal Infection of the Nail

Onychomycosis:Fungal Infection of the Nail Onycholysis:Separation of Nail from Underlying Bed, often due to onychomycosis

Onycholysis:Separation of Nail from Underlying Bed, often due to onychomycosis Paronychia:Infection of skin adjacent to nail of middle finger

Paronychia:Infection of skin adjacent to nail of middle finger - Capillary refill: This is a mechanism for gauging arterial perfusion. Press

the nail bed or tip of any finger for several seconds, causing the underlying

skin to whiten. After releasing pressure, the normal pink color should return

in 2-3 seconds. Delay implies under perfusion. Interestingly, while atherosclerotic

vascular disease is a common cause of arterial insufficiency in the lower

extremity, it rarely occurs in the arms or hands. Thus, delayed capillary

refill in the hands more likely reflects vasospasm or hypovolemia then it

does intraluminal arterial obstruction. Severe vasospasm, referred to as Raynaud's

Phenomenon, occurs most frequently in women after exposure to cool temperatures,

causing both hands to become white and painful.

For Additional Information See: Digital DDx: Finger Pain, Ischemia, Ulcers

Peripheral Vascular Disease, HandTissue death (i.e. gangrene) of the fingers secondary to severe peripheral vascular disease.

Peripheral Vascular Disease, HandTissue death (i.e. gangrene) of the fingers secondary to severe peripheral vascular disease. - Temperature: Cool hands occur most commonly as a result of exposure to a cold environment. However, this can also reflect vascular insufficiency, vasospasm, or hypovolemia.

- Obvious joint abnormalities, noting particularly if there is a specific

pattern or distribution. For example, deformity of the metacarpal-phalyngeal

joints on every finger of both hands is consistent with a systemic inflammatory

process like Rheumatoid Arthritis. An isolated abnormality of a single, distal

joint, however, is more likely secondary to local trauma or degenerative arthritis.

Joint deformities secondary to rheumatoid arthritis

And a few words about uncommonly encountered abnormalities... The presence or absence of these findings are frequently mentioned in clinical medicine, giving the impression that they are common and/or of great importance. This is more myth then fact as most patients with the disease states in question do not have these findings. Their clinical utility tends to be over emphasized.

-

Clubbing: Bulbous appearance of the distal phalanges of all fingers along with

concurrent loss of the normal angle between the nail base and adjacent skin.

This is most commonly associated with conditions that cause chronic hypoxemia

(e.g. severe emphysema), though it is also associated with a number of other

conditions. However, in general it is neither common nor particularly sensitive

for hypoxia, as most hypoxic patients do not have clubbing.

- Cyanosis: A bluish discoloration visible at the nail bases

in select patient with severe hypoxemia or hypoperfusion. As with clubbing,

it is not at all sensitive for either of these conditions.

- Splinter Hemmorrhages: Short, thin, brown, linear streaks in the nails of some patients (the minority) with endocarditis.

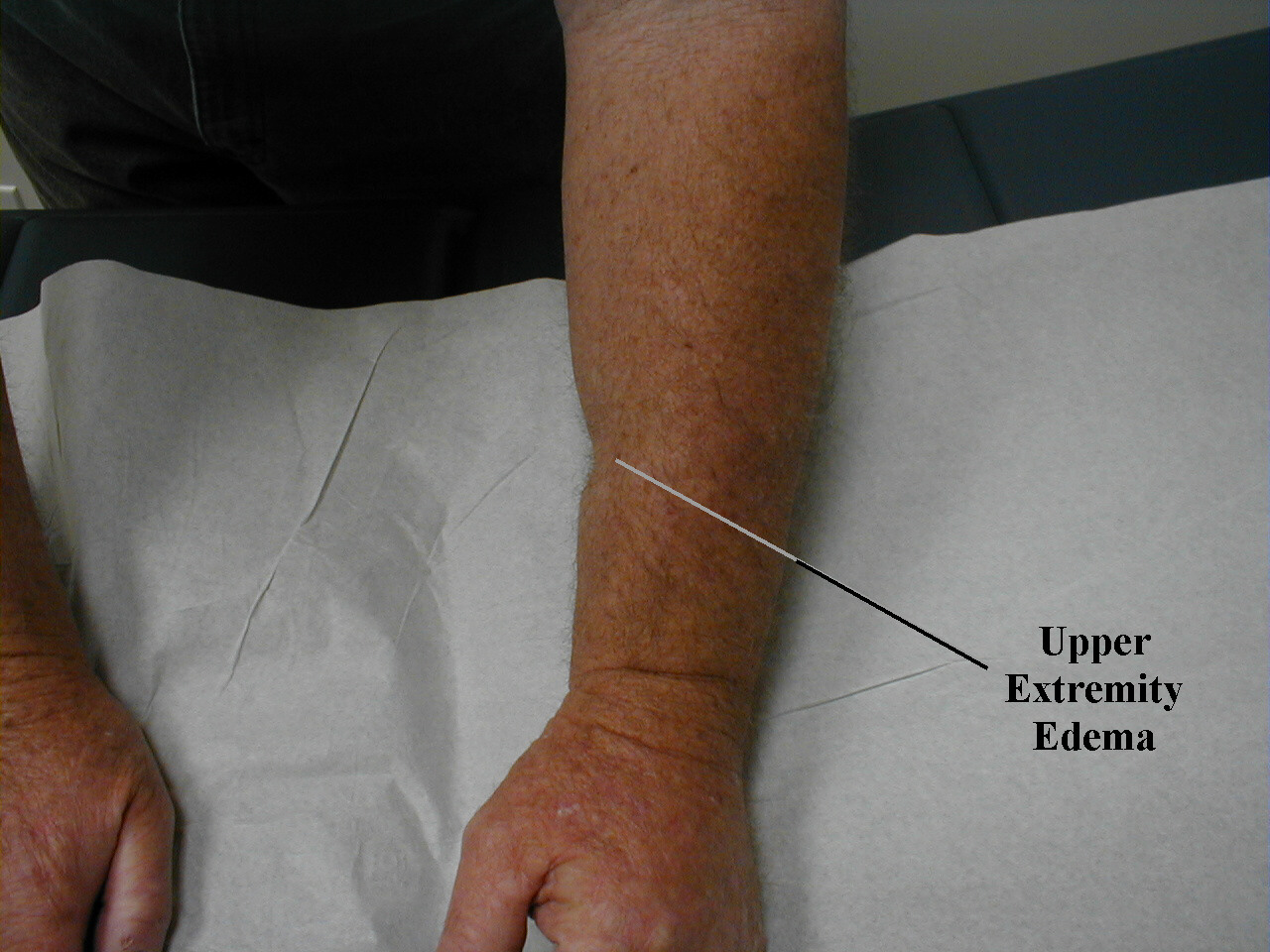

- Edema: While edema is a relatively common finding in the lower extremity,

it rarely occurs in the arms and hands. This is because the lower extremities

are exposed to greater hydrostatic pressure due to their dependent position.

Upper extremity edema, when present, usually occurs focally over an area of

local inflammation (e.g. cellulitis). Diffuse arm edema can occur if drainage

is compromised, as when the lymphatics are disrupted following axillary lymph

node surgery for staging and treatment of breast cancer. Upper extremity venous

obstruction can also cause edema, though blood clots in this region are much

less common then in the lower extremity.

Note divit left (pitting) after application of pressure.

Note divit left (pitting) after application of pressure.

Edema in this case is due to lymphatic obstruction. Right upper extremity DVT. Note diffuse swelling.

Right upper extremity DVT. Note diffuse swelling.

-

Clubbing: Bulbous appearance of the distal phalanges of all fingers along with

concurrent loss of the normal angle between the nail base and adjacent skin.

This is most commonly associated with conditions that cause chronic hypoxemia

(e.g. severe emphysema), though it is also associated with a number of other

conditions. However, in general it is neither common nor particularly sensitive

for hypoxia, as most hypoxic patients do not have clubbing.

In the setting of injury or infection, the affected area should be examined in greater detail. For example, acute inflammation secondary to cellulitis of the upper extremity is demonstrated in the image below.

Lymph Nodes of the Upper Extremity:

Epitrochlear Nodes: Found on the inside of the upper arm, just above the elbow. These are rarely the site of pathology and thus not routinely examined. If there is clinical evidence of an infection distal to the elbow, it makes sense to feel for these nodes as they are part of the drainage pathway. To examine, cup the patient's elbow in your hand (left elbow with right hand and vice versa) and palpate just above the elbow, along the inside of the upper arm. When inflamed, the nodes become large and tender.

For Additional Information See: Digital DDx: Adenopathy

Axillary Nodes: Pathologic enlargement occurs most commonly in the following settings:

- Infection:

- systemic (e.g. TB, HIV)

- local (e.g. cellulitis of the hand/arm)

- Malignancy:

- lymphoma, where the malignacy is based in lymph nodes

- metastases, in particular breast, though could be from any site

- Other:

- various systemic inflammatory illnesses (e.g sarcoidosis)

When examining healthy individuals, both axilla can be examined simultaneously. To do this, ask the patient to lift both arms away from the sides of their body. Then extend the fingers of both your hands and gently direct them towards the apices of the arm pits. You can do this through the patients gown if you don't want to place your fingers in direct contact with the axilla. Now press your hands towards the patient's body and move them slowly down the lateral chest wall. This allows you to explore the axillary regions in their entirety.

If you feel any abnormalities, repeat the exam of each axilla separately. When examining the left axilla, grasp the patient's left wrist or elbow with your left hand and lift their arm up and out laterally. Then use your right hand to examine the axillary region as described above. This technique permits the patient's arm to remain completely relaxed, minimizing tension in the surrounding tissues that can mask otherwise enlarged lymph nodes. The right axilla is examined in a similar fashion, though hand positioning is reversed. This examination may also be performed while the patient is supine, as would be done if you were to couple it with the female breast exam.

Most patients do not have palpable axillary nodes. If you are able to feel adenopathy, make note of the following characteristics:

- Size: Pathologic nodes are generally greater than 1 cm

- Firmness: Malignancy makes nodes feel harder

- Quantity: The greater the number of nodes, the more likely true pathology exists

- Pain: Often associated with inflammation (e.g. infection)

- Relation to other nodes and surrounding tissue: Nodes fixed to each other or adjacent structures are worrisome for malignancy

- Changes over time: Nodes which regress spontaneously are obviously of less concern then those that increase in size, number, or appear to be growing in new locations. Making these determinations requires multiple evaluations over time.